TROMSØ, Norway — Extreme snowstorms resulting from climate change are leaving entire populations of Antarctic seabird colonies unable to breed, new research explains. Researchers from Norway say a rise in unusually strong blizzards means there is nowhere for the birds to safely lay their eggs and nest — putting them at risk for extinction in the future.

The breeding grounds, which stretch across hundreds of miles and once held nests numbering in the tens of thousands, are now barren of nests that were home to south polar skua, Antarctic petrel, and snow petrel. Scientists from the Norwegian Polar Institute also warn that they expect these storms to worsen in severity, causing concerns for the populations of these seabirds in the coming decades.

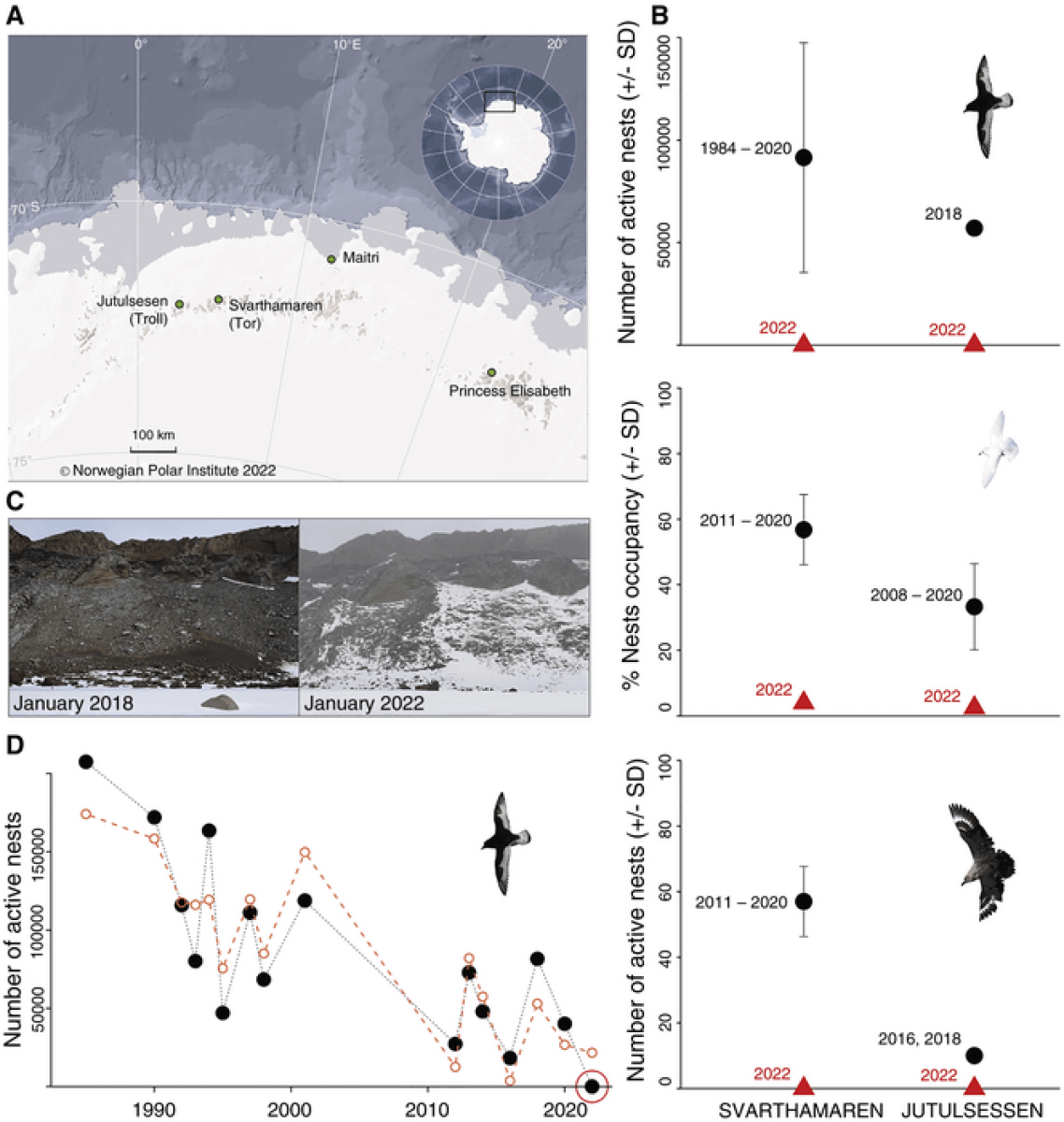

The study, published in the journal Current Biology, focused on the Antarctic mountain regions of Svarthamaren and nearby Jutulsessen. The regions are home to two of the world’s largest Antarctic petrel colonies and are essential nesting grounds for seabirds like snow petrels and south polar skua.

From 200,000 to just 3 nests?

In the 35 years from 1985 to 2020, the colony in Svarthamaren played host to between 20,000 and 200,000 Antarctic petrel nests, around 2,000 snow petrel nests, and over 100 skua nests each year. The Antarctic birds’ prime breeding time starts at the beginning of the year — the perfect time to lay their eggs and build their nests.

However, in the breeding season between December 2021 and January 2022, there were just three breeding Antarctic petrels, only a handful of breeding snow petrels, and not a single south polar skua nest at Svarthamaren. The researchers similarly found that in nearby Jutulsessen there were no Antarctic petrel nests between the summer of 2021 and the beginning of the new year, despite there being tens of thousands of active nests in the area in previous years.

The study’s authors explain that because the birds lay their eggs on bare ground, too much snow makes the ground inaccessible and renders the raising of chicks impossible. They add that the birds also have to use their available energy to keep warm and shelter from the extreme snow and winds.

Sebastien Descamps, the lead author of the study, says that whilst the storms have always made breeding more difficult for the seabirds, these low results were shocking and unexpected.

“We know that in a seabird colony, when there’s a storm, you will lose some chicks and eggs, and breeding success will be lower,” says Descamps, first author of the study and researcher at the Norwegian Polar Institute, in a media release. “But here we’re talking about tens if not hundreds of thousands of birds, and none of them reproduced throughout these storms. Having zero breeding success is really unexpected.”

“It wasn’t only a single isolated colony that was impacted by this extreme weather. We’re talking about colonies spread over hundreds of kilometers,” says Descamps. “So these stormy conditions impacted a really large part of land, meaning that the breeding success of a large part of the Antarctic petrel population was impacted.”

Global weather patterns will only get more extreme

Although researchers didn’t initially notice the climactic shifts in the Antarctic, recent extreme weather across the region has begun to provide worrying evidence of these changes. Forecasts of these extreme weather events are only projecting them to increase in frequency in the coming years.

“Until recently, there were no obvious signs of climate warming in Antarctica except for on the peninsula,” Descamps adds. “But in the last few years, there have been new studies and new extreme weather events that started to turn the way we see climate change in Antarctica.”

“When it comes to storm severity, it’s both the wind and the snow accumulation,” the researcher continues. “There aren’t many places where we have the right kinds of snow measurements, and it plays an important role in explaining the breeding success of the birds.”

“I think our study shows in a very strong way that these extreme events do have a very strong impact on seabird populations, and climate models predict that the severity of these extreme events will increase.”

South West News Service writer James Gamble contributed to this report.

This is nonsense. The data shows there is no indication weather is becoming more extreme.