NEW YORK — An Earth-sized planet dubbed “hell” got so devilishly hot because it orbits along its star’s equator, according to new research.

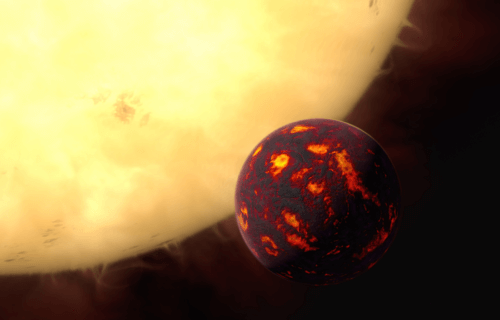

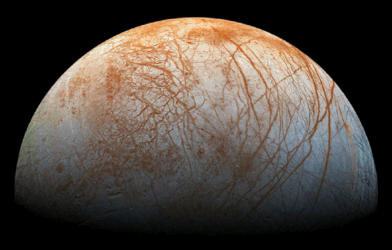

The entire surface of this “super-Earth” is an ocean of lava that reaches temperatures of around 2,000 degrees Celsius. Nicknamed “Janssen,” the rocky world is one of the most exotic discovered outside our solar system.

It’s also known as the diamond planet because its interior is abundant in carbon, which creates the precious gemstones under extreme pressure. The new insights come from a space exploration tool that captured ultra-precise measurements of starlight from Janssen’s home star, Copernicus.

The discovery has implications for alien hunters. Such information is critical to finding out just how common Earth-like environments are and how abundant extraterrestrial life may be in the universe.

“We’ve learned about how this multi-planet system — one of the systems with the most planets that we’ve found — got into its current state,” says study lead author Lily Zhao, a research fellow at the Flatiron Institute’s Center for Computational Astrophysics (CCA), in a media release.

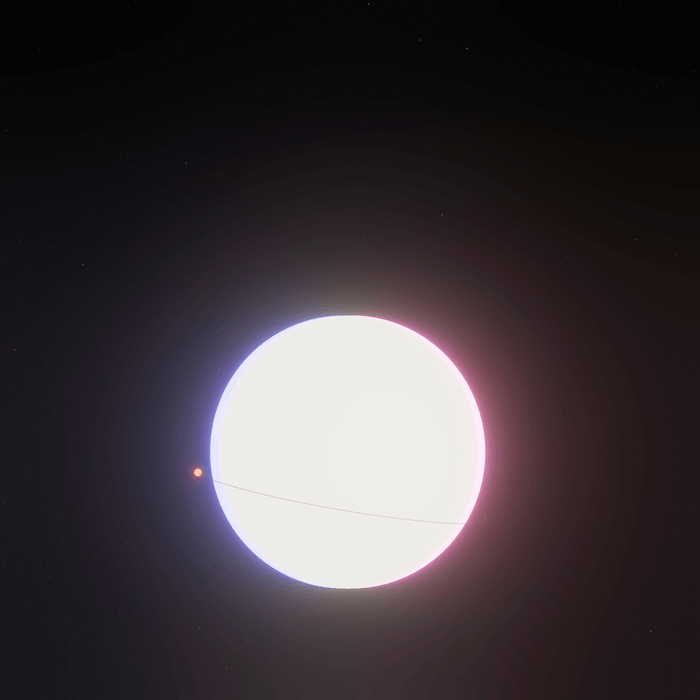

Copernicus’ other planets are on such different orbital paths that they never even cross between the star and Earth. The light measurements ever-so-slightly shifted as Janssen moved between Earth and the star — akin to our moon blocking the sun during a solar eclipse.

It suggests the planet formed in a relatively cooler orbit further out, slowly falling toward Copernicus over time. Janssen’s path altered as it moved closer in. Even in its original orbit, the planet “was likely so hot that nothing we’re aware of would be able to survive on the surface,” says Dr. Zhao.

Scientists hope their study in the journal Nature Astronomy will improve understanding of how planets form and move around over eons.

Janssen was discovered in 2004, making it the first known “super-Earth.” It is about eight times as massive and twice as wide as our planet. The atmosphere is rich in hydrogen. There is also helium, and potentially, hydrogen cyanide. It is the first exoplanet, that we know of, to have an atmosphere — despite its hellish surface.

Janssen’s orbit has a minimum radius of roughly two million kilometers. For comparison, Mercury’s is 46 million and Earth’s 147 million.

Astronomers believe the planet formed about eight billion years ago. Its orbit is so snug around Copernicus, astronomers first doubted its existence. As Copernicus rotates, half the star is twirling toward us, and the other half is moving away.

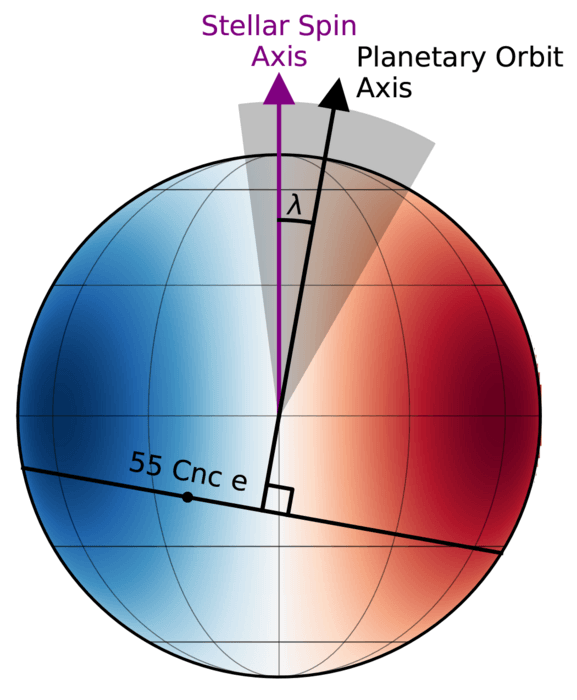

That means half the star is a bit bluer, and the other half is slightly redder — with the space in the middle unshifted. So, astronomers can track Janssen by measuring when it is blocking light from the redder side, the bluer side, and the unaltered midsection.

However, the resulting difference in the starlight is almost immeasurably small. The breakthrough came from the EXPRES (EXtreme PREcision Spectrometer). The device at the Lowell Discovery Telescope in Arizona offered the sensitivity needed to notice the tiny red and blue shifts.

The EXPRES measurements revealed Janssen’s orbit is roughly aligned with Copernicus’ equator, a path that makes it unique. Interactions shifted Janssen toward its hellish present-day location. As Janssen approached Copernicus, the star’s gravity became increasingly dominant.

Because Copernicus is spinning, the centrifugal force caused its midsection to bulge outward slightly and its top and bottom to flatten. That affected the gravity felt by Janssen, pulling the planet into alignment with the star’s thicker equator.

“We’re hoping to find planetary systems similar to ours,” Zhao says, “and to better understand the systems that we do know about.”

Super-Earths are the most common type of planet in our galaxy, though none exist in our solar system. They are called super-Earths because they have more mass than our world but are smaller than the system’s gas giants. A greater understanding of super-Earths should mean a greater understanding of the most common type of planet around.

South West News Service writer Mark Waghorn contributed to this report.

We’re not going there any time soon.