WASHINGTON — A new method of freezing human embryos could result in better in vitro fertilization (IFV) outcomes and give new hope to childless couples. A new study finds the system, which protects eggs from freezing damage, could make IFV simpler and less prone to human error.

The CDC says assisted reproductive technology cycles, which includes IVF treatments, contributed to nearly 74,000 U.S. births in 2018. Just under two percent of all births in the U.S. each year involve assisted reproductive technology.

Typically, women have to go through weeks of hormone therapy before having an operation to retrieve their egg cells. These precious eggs are fertilized with a sperm cell in vitro, meaning outside the body. The fertilized egg, now an embryo, is then be transferred into a woman’s uterus.

Not every IVF procedure goes as planned

While doctors select only the best embryos, not all transfers are a success. Therefore, it’s become common practice to freeze the extra embryos for safe keeping. This allows women who face fertility risks due to age or treatments like chemotherapy to delay the process.

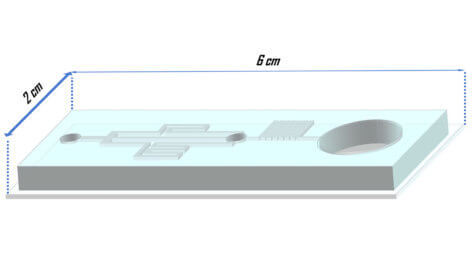

For this to work, fertility experts must replace the water inside the embryo with a substance which protects it from freezing damage – a cryoprotectant. However, suddenly removing the water would kill the embryo, so technicians must do this a few droplets at a time. Now, researchers have discovered a way to make freezing eggs a breeze using what they call a standalone microfluidics system.

“What if embryos simply stayed in the same place, and cryoprotectants were brought to them? Microfluidics systems are really good at controlling flow and concentration,” study author and assistant professor Mojtaba Dashtizad at the National Institute of Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology in Iran says in a media release.

New procedure creates a slow and steady way to freeze eggs

The setup has a chamber for the embryo and three channels to gradually introduce the freeze protection. At the same time, any water is drained through an exit channel, until the concentration of cryoprotectants is just right. Researchers say this means once the embryo is inside the chamber, technicians can sit back and relax. Unlike traditional methods, the new system ensures embryos are exposed to a slow and constant increase in cryoprotectant.

“Our genetic studies show this reduces molecular damage caused by cryopreservation,” Dashtizad adds. “And embryos can be cryopreserved faster and with a lower concentration of cryoprotectants — a huge advantage because of the toxicity of these chemicals.”

It also makes the process simpler and easier to follow, reducing the risk of human error.

“Our findings emphasize the importance of moving away from droplet-based loading of cryoprotectants to gradual concentration controls,” the study author concludes. “These can ultimately reduce damage to embryos during the cryoprocedure, and it moves us one step closer to increasing the efficiency of assisted reproduction and the improved health of future babies.”

The findings appear in the journal Biomicrofluidics.

SWNS writer Tom Campbell contributed to this report.