RICHMOND, Va. — Ovarian cancer can be devilishly tricky to diagnose in its early stages when treatment is most effective. That’s because the symptoms—bloating, constipation, back pain—are maddeningly vague and resemble far more common problems. Scientists are now on the verge of making early detection of ovarian cancer much simpler thanks to a urine test under development.

There’s no standard screening test for ovarian cancer like the mammogram for breast cancer or colonoscopy for colon cancer. The blood test for CA-125 can detect the disease, but it also gives false positives. And less than 20% of ovarian tumors produce enough of the protein for the test to be reliable. Ultrasounds and other imaging tests also miss far too many early-stage cases.

“Clinical data shows a 50-75% improvement in 5-year survival when cancers are detected at their earliest stages. This is true across numerous cancer types,” says Joseph Reiner, Ph.D., a researcher at Virginia Commonwealth University, in a statement.

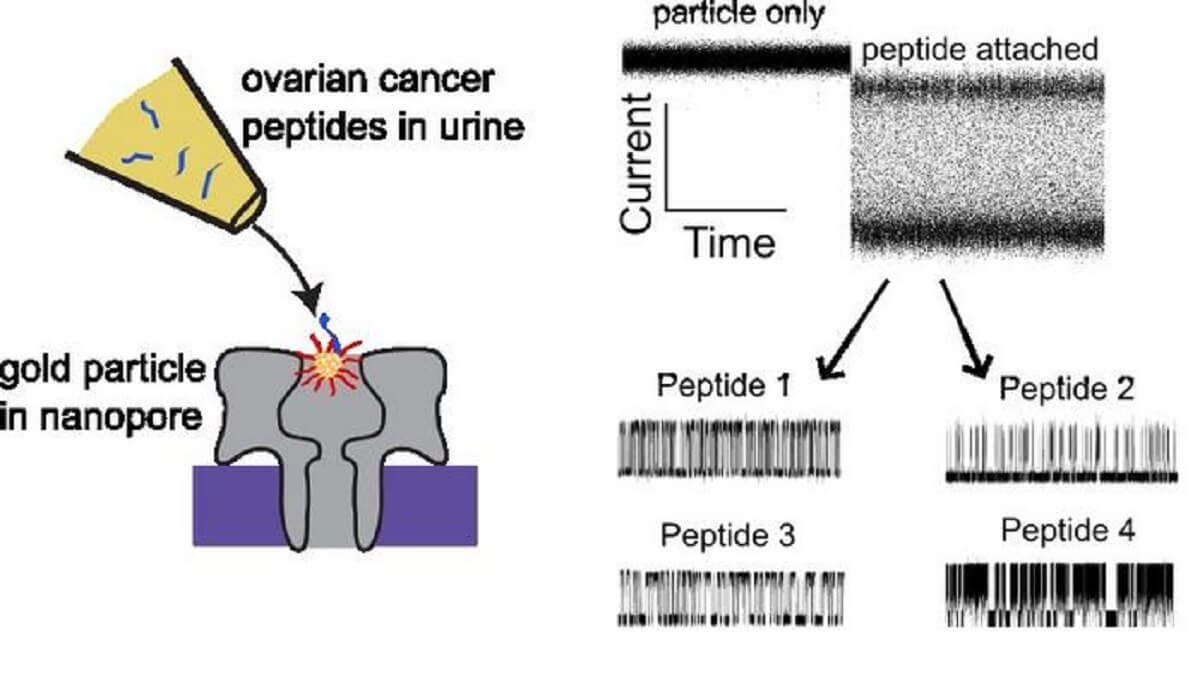

But Reiner is working on a promising new diagnostic tool that could revolutionize early detection of ovarian cancer and give many more women a fighting chance against this deadly disease. His team has developed a urine test that can spot the presence of ovarian cancer by identifying certain peptides, or protein fragments, that previous studies have shown are plentiful in the urine of women with ovarian tumors.

The challenge has been finding an affordable way to reliably detect those peptides. Reiner had a lightbulb moment when he realized he might be able to harness nanopore sensor technology to “basically count and identify peptides that are shed from ovarian cancer tissue into the urine.”

Here’s how it works: Urine samples are exposed to tiny nanopores—essentially holes a few billionths of a meter wide. An electrical current runs across the nanopores, and molecules from the urine sample pass through these holes, each giving off a distinctive electrical signal. The nanopores in Reiner’s test are coated with gold nanoparticles, which interact with and alter the signal of cancer-related peptides in ways that act as detection “fingerprints.”

So far, Reiner has identified signatures from 13 peptides associated with ovarian cancer, including LRG-1, an ovarian cancer biomarker already in use. “We now know what those signatures look like, and how they might be able to be used for this detection scheme,” he explains. “It’s like a fingerprint that basically tells us what the peptide is.”

The test is still in early development. But the ability to spot multiple cancer peptides at once could make it more sensitive than current options. Reiner hopes his ovarian cancer screen may eventually be used along with other information to improve early diagnosis.

That could make a life-saving difference to the thousands of women newly diagnosed with ovarian cancer each year. Earlier detection from this promising new screening approach may soon give them better odds of beating this challenging disease.

These findings were presented at the Biophysical Society Annual Meeting in Philadelphia.