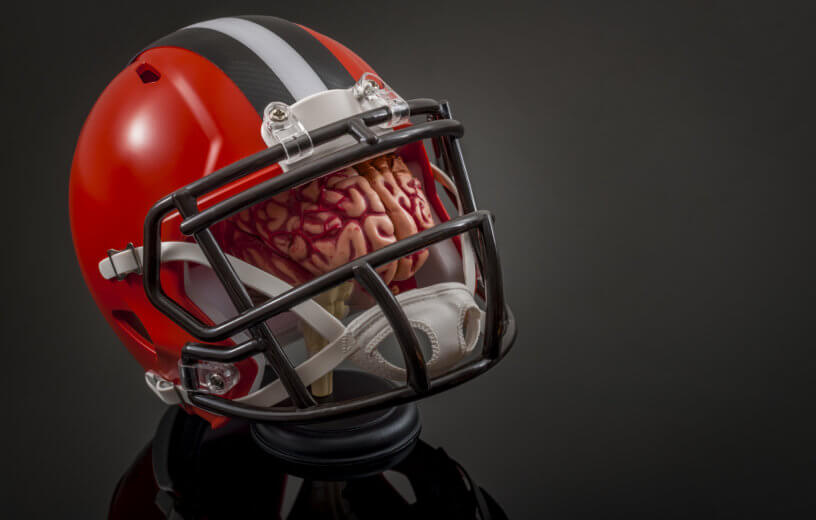

EXETER, United Kingdom — Suffering a third concussion could be the point of no return when it comes to healthy brain functioning later in life. Researchers in the United Kingdom say multiple concussions can affect memory, and the ability to focus, process information, and complete complex tasks. Even suffering from just one moderate or severe concussion or traumatic brain injury could have a long-term impact on the brain.

Moreover, researchers say with each new concussion the impact gets worse. These findings shed light on the dangers of high-risk sports such as rugby, football, boxing. They also come just weeks after the death of Scottish rugby player Doddie Weir, who developed motor neuron disease.

“The 2016–17 Professional Rugby Injury Surveillance Project reported concussion to be the most commonly reported rugby match injury in English Premiership Clubs and the England Senior team, contributing to 22 percent of all match injuries,” according to the Drake Foundation, a nonprofit organization that works to improve the health and welfare of people impacted by head injuries. “During the 2016–17 season a total of 169 match concussions were reported.”

“We know that head injuries are a major risk factor for dementia, and this large-scale study gives the greatest detail to date on a stark finding – the more times you injure your brain in life, the worse your brain function could be as you age,” says lead investigator Dr. Vanessa Raymont from the University of Oxford in a media release.

“Our research indicates that people who have experienced three or more even mild episodes of concussion should be counselled on whether to continue high-risk activities. We should also encourage organizations operating in areas where head impact is more likely to consider how they can protect their athletes or employees.”

Even 1 concussion damages a patient’s attention span

The team in this new study took data from over 15,000 participants based in the U.K. They were between the ages of 50 and 90. Each person reported the severity and frequency of concussions they had experienced throughout their lives and took part in annual, computerized brain function tests.

The participants who reported three episodes of even mild concussions in their lives had significantly worse attention and ability to complete complex tasks. Those who had four or more mild concussion episodes also showed a drop in their processing speed and working memory.

The team also found that reporting even one moderate-to-severe concussion displayed a link to worsening attention span and a drop in the patient’s ability to complete complex tasks and process information. The team linked each additional reported concussion to progressively worsening cognitive function. The study offers a goldmine of data to help understand how the brain ages and the factors involved in maintaining a healthier brain in later life.

“As our population ages, we urgently need new ways to empower people to live healthier lives in later life,” says study co-author Dr. Helen Brooker from the University of Exeter.

“This paper highlights the importance of detailed long-term studies like PROTECT in better understating head injuries and the impact to long term cognitive function, particularly as concussion has also been linked to dementia. We’re learning that life events that might seem insignificant, life experiencing a mild concussion, can have an impact on the brain. Our findings indicate that cognitive rehabilitation should focus on key functions such as attention and completion of complex tasks, which we found to be susceptible to long-term damage.”

“Studies like this are so important in unravelling the long-term risks of traumatic brain injury, including their effect on dementia risk. These findings should send a clear message to policy makers and sporting bodies, who need to put robust guidelines in place that reduce risk of head injury as much as possible,” adds Dr. Susan Kohlhaas, Director of Research at Alzheimer’s Research UK.

The study is published in the Journal of Neurotrauma.

South West News Service writer Alice Clifford contributed to this report.