DURHAM, N. C. — It can happen to the best of us. The checkbook doesn’t balance this month or we avoid paying with cash because it involves too much thinking. But trouble managing money can also mean dementia is on the horizon, according to a new Duke University study.

“There has been a misperception that financial difficulty may occur only in the late stages of dementia, but this can happen early, and the changes can be subtle,” says senior author P. Murali Doraiswamy, MBBS, a professor of psychiatry and geriatrics at the university, in a university release.

Researchers believe that one of the keys to managing potential trouble is to have a baseline of one’s typical financial management abilities so it becomes easier to spot changes.

Study authors considered data from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, a longitudinal study of 243 adults ages 55 to 90. Participants were a mix of cognitively healthy adults, adults with mild memory impairment and adults with an Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis.

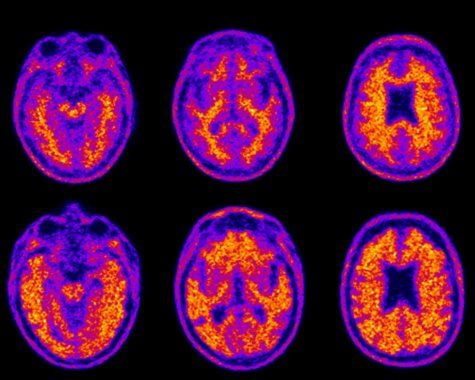

Tests that participants had completed as part of the longitudinal study demonstrated their scores on financial skills. Brain scans showed levels of protein buildup of beta-amyloid plaques in their brains.

Results of the study found that certain financial skills decline as the years go by, yes, but also can signal the very first stages of mild memory impairment.

After controlling results for educational levels and other demographics, researchers found a direct relationship between increased amyloid plaques and a reduced ability to comprehend basic financial concepts or to complete such mathematical tasks as calculating an account balance. Both men and women experienced similar declines.

Researchers point out that even cognitively healthy adults can end up with more protein plaques as part of the aging process. But for adults with mild memory impairment or a family history of Alzheimer’s disease, these plaques may develop earlier and be more aggressive.

Researchers say most tests for early dementia and Alzheimer’s focus on memory. They believe financial assessment tools — such as the Financial Capacity Instrument-Short Form used in this study — could be another way to catch small changes in abilities before they become big problems. They would also like to see doctors become more proactive with testing and counseling patients about any subtle changes in cognitive function.

“Older adults hold a disproportionate share of wealth in most countries and an estimated $18 trillion in the U.S. alone,” Doraiswamy warns. “Little is known about which brain circuits underlie the loss of financial skills in dementia. Given the rise in dementia cases over the coming decades and their vulnerability to financial scams, this is an area of high priority for research.”

The study is published in The Journal of Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease.