WASHINGTON — Fresh meat typically means better safety and quality. Thanks to advancements in technology that help extend shelf life, meat can be shipped around the world and eaten long after the animal dies. Still, as the demand for meat continues to increase globally, so does the demand for efficient measures that address problems like rotting and bacteria. With that in mind, scientists have created a new sensor that can tell if the meat in your refrigerator is still fresh or headed for the garbage.

Even with strong efforts, it’s still impossible to address all of the aging processes in meat. Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is a molecule produced by breathing and gives energy to cells. Once an animal stops breathing, synthesis of ATP stops, and the molecules break down into acid. Flavor and then safety go away soon after. During the transition, there are two steps: hypoxanthine (HXA) and xanthine. By looking at their prevalence in meat, researchers can determine the level of freshness.

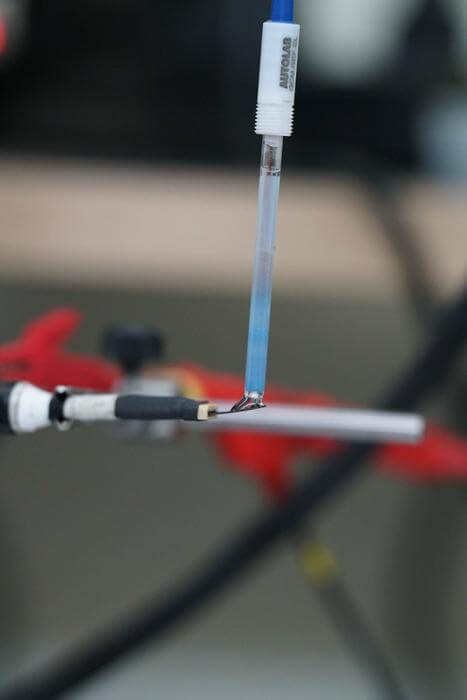

Researchers from the Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology, VNU University of Science, Hanoi University of Science and Technology, and the Russian Academy of Sciences developed a biosensor with graphene electrodes modified by zinc oxide nanoparticles to measure HXA by using pork meat.

“In Vietnam, pork is the most consumed meat,” says author Ngo Thi Hong Le, in a media release. “Therefore, pork quality monitoring is one of the important requirements in the food industry in our country, which is why we prioritized it.”

Currently, there are several HXA sensing methods that exist. However, they can be pricey and impractical.

“In comparison to modern food-testing methods, like high-performance liquid chromatography, gas chromatography, mass spectrometry, atomic and molecular spectroscopy, and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, biosensors like our sensor offer superior advantages in time, portability, high sensitivity, and selectivity,” says Le.

Researchers made the sensor using a polyimide film, which is converted into porous graphene with the help of a pulsed laser. The zinc oxide nanoparticles attract the HXA molecules to the electrode surface and undergoes oxidation reactions to transfer electrons and spike the voltage. The relationship between HXA and voltage increase allows researchers to note HXA content. Although the team used it with pork, it can be used with any variety of meat.

To put the sensor to the test, the team started experimenting with known amounts of HXA. After a remarkable response, they measured the ability to perform using pork tenderloins purchased from a market. The sensor responded with over 98 percent accuracy. These findings are promising and could strengthen food safety measures around the world with more validating research.

The findings are published in AIP Advances.

A Dietitian’s Take

It’s important to practice food safety from farm to table with all foods, but especially meat. As a registered dietitian, I’ve noticed a startling trend where more and more people are eating raw meat. This is either to be edgy or because of supposed health benefits that cooked meat doesn’t have.

The reality is that nutrients remain largely intact in cooked meat, it’s just a good rule of thumb to not burn it. Moreover, it’s better to cook meat than risk illness, even if you think what you’re buying is super fresh. Although dishes like tartare are popular in certain cuisines, these dishes are usually prepared with fresh meats and higher levels of food safety that the average person may not be doing at home.

Luckily, especially in the United States, there is plenty of technology that helps support meat safety during production. A biosensor that’s more affordable and practical like the one in this study could take things to the next level, and it’ll be interesting to see where it goes.

You might also be interested in: