SALT LAKE CITY — “Magic mushrooms” have long shown promise in treating mental health conditions, but now, the largest genomic diversity study of these fungi is offering new insights into its evolution and potential therapeutic uses. Researchers from the University of Utah and the Natural History Museum of Utah (NHMU) delved into the Psilocybe genus, which contains the psychoactive compounds psilocybin and psilocin, and found it originated around the time when dinosaurs went extinct.

Until now, scientific understanding of these compounds was limited, based on only a fraction of the approximately 165 known Psilocybe species. This study’s genomic analysis of 52 Psilocybe specimens, including 39 never-before-sequenced species, marks a significant step forward.

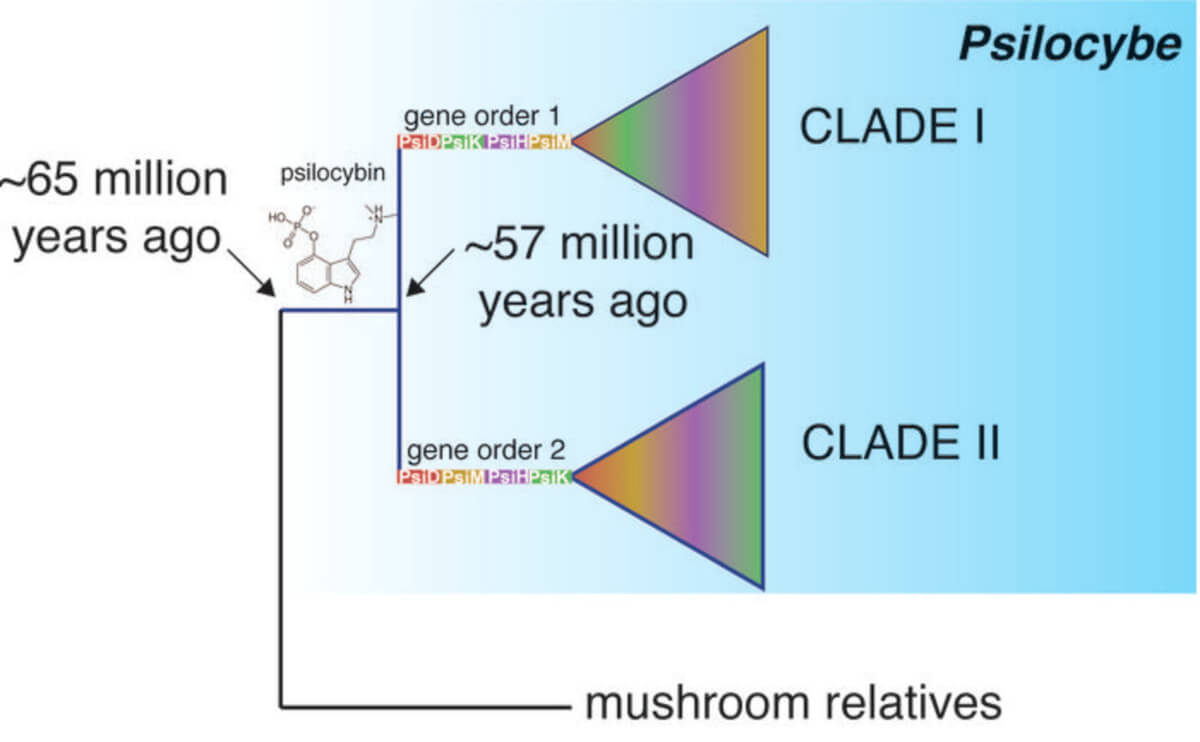

The researchers discovered that Psilocybe originated around 65 million years ago, coinciding with the asteroid strike that led to the extinction of dinosaurs. This finding challenges previous assumptions about the fungi’s age. The study also reveals that psilocybin first synthesized in mushrooms in the Psilocybe genus, with four to five horizontal gene transfers to other mushrooms occurring between nine and 40 million years ago.

An intriguing aspect of the study is the identification of two distinct gene orders within the gene cluster that produces psilocybin, indicating two independent acquisitions of psilocybin in the genus’s evolutionary history.

“If psilocybin does turn out to be this kind of wonder drug, there’s going to be a need to develop therapeutics to improve its efficacy. What if it already exists in nature?” says study senior author Bryn Dentinger, curator of mycology at NHMU, in a university release. “There’s a wealth of diversity of these compounds out there. To understand where they are and how they’re made, we need to do this kind of molecular work to use biodiversity to our advantage.”

The study also utilized “type specimens” from museum collections worldwide. These specimens are considered the gold standard in taxonomy, serving as reference points for identifying species. The molecular work on these type specimens is a critical contribution to the field of mycology, providing a reliable foundation for future research on Psilocybe diversity.

Researchers also explored the potential roles of psilocybin in mushrooms. While its molecular structure mimics serotonin and binds tightly to serotonin receptors in mammals, the exact benefits to the mushrooms remain unclear. Some theories suggest it could be a deterrent to predation or a chemical defense against insects, but empirical evidence is lacking.

The authors are preparing experiments to test the Gastropod Hypothesis, which posits that psilocybin may have evolved as a deterrent to slugs, a significant predator of mushrooms. This hypothesis aligns with the timing of Psilocybe’s divergence around 65 million years ago, following the asteroid impact and a period of massive diversification and proliferation of terrestrial gastropods.

“It’s impossible to overstate the importance of collections for doing studies like this. We are standing on the shoulders of giants, who spent thousands of people-power hours to create these collections, so that I can write an email and request access to rare specimens, many of which have only ever been collected once, and may never be collected again,” says study lead author Alexander Bradshaw, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Utah.

With plans to sequence every Psilocybe type specimen, researchers continue to collaborate with collections globally, shedding light on the mysterious and potentially therapeutic world of magic mushrooms.

The study is published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.