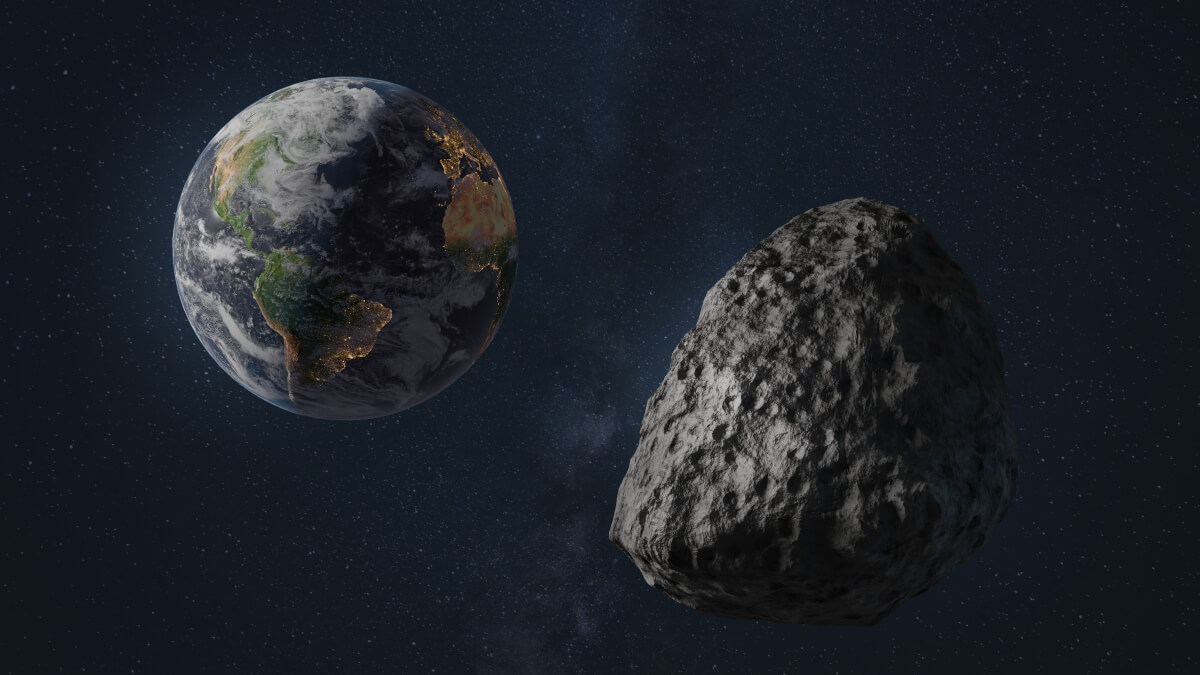

PERTH, Australia — A giant asteroid hurtling toward Earth sounds like the apocalypse is coming, but astronomers in Australia say there may be nothing to worry about. At Curtin University, astronomers studying an ancient asteroid say the samples of rubble and space dust are giving them a good idea of what type of asteroids would most likely approach our planet. More importantly, it’s giving them an idea of how to stop them.

The research team collected three tiny dust samples from the surface of an ancient asteroid named Itokawa. The asteroid is two million kilometers (over 1.2 million miles) from Earth and is 500 meters long (1,640 feet). Researchers say this giant space rock is almost as old as the solar system and has become both hard to destroy and resistant to collisions.

“Unlike monolithic asteroids, Itokawa is not a single lump of rock, but belongs to the rubble pile family which means it’s entirely made of loose boulders and rocks, with almost half of it being empty space,” says Fred Jourdan, director of the Western Australian Argon Isotope Facility, part of the John de Laeter Centre and the School of Earth and Planetary Sciences at Curtin University, in a university release.

Astronomers estimate Itokawa formed 4.2 billion years ago after a huge space collision broke it away from its larger, parent asteroid. For an asteroid like Itokawa to survive this long, it must consist of a durable and shock-absorbent material.

“In short, we found that Itokawa is like a giant space cushion, and very hard to destroy,” Jourdan reports.

Can scientists really nuke an asteroid like in the movies?

The team used two techniques to study the three dust samples. The first is called Electron Backscattered Diffraction, which allows scientists to study the microstructure of an object. Analyzing the internal structure lets astronomers measure if a rock has absorbed shock from a meteor collision. The second method is called argon-argon dating and it helps scientists date when these impacts occurred.

Before this study, there was little knowledge of the durability of rubble pile asteroids. This makes it hard to predict if one of these ancient asteroids would crumble upon impact or absorb the shock and cause considerable damage if they ever struck Earth.

“Now that we have found they can survive in the solar system for almost its entire history, they must be more abundant in the asteroid belt than previously thought, so there is more chance that if a big asteroid is hurtling toward Earth, it will be a rubble pile,” says Nick Timms, an associate professor from Curtin’s School of Earth and Planetary Sciences.

“The good news is that we can also use this information to our advantage – if an asteroid is detected too late for a kinetic push, we can then potentially use a more aggressive approach like using the shockwave of a close-by nuclear blast to push a rubble-pile asteroid off course without destroying it.”

The study is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.