Does Taylor Swift’s music belong in the English classroom? No, obviously. We should teach the classics, like Shakespeare’s Sonnets. After all, they have stood the test of time. It’s 2024 and he was born in 1564, and she’s only 34. What’s more, she is a pop singer, not a poet. Sliding her into the classroom would be yet another example of a dumbed-down curriculum. It’s ridiculous. It makes everyone look bad.

I’ve heard all that. And plenty more like it. But none of it is right. Well, the dates might be, but not the assumptions – about Shakespeare, about English, about teaching, and about Swift.

Swift is, by the way, a poet. She sees herself this way and her songs bear her out. In Sweet Nothing, on the Midnights album, she sings:

On the way home

I wrote a poem

You say “What a mind”

This happens all the time.

I’m sure it does. Swift is relentlessly productive as a songwriter. With Midnights, she picked up her fourth Grammy for Album of the Year. And here we are, on the brink of another studio album, The Tortured Poets Department, somehow written and produced amid the gargantuan success of Midnights and the Eras World Tour.

An ally of literature

Regardless of what The Tortured Poets Department ends up being about, Swift is already a firm ally of literature and reading. She is a donor of thousands of books to public libraries in the United States, an advocate to schoolchildren of the importance of reading and songwriting, and a lover of the process of crafting lyrics.

In a 2016 Vogue interview, Swift declared with glee that, if she were a teacher, she would teach English. The literary references in her songs are endlessly noted. “I love Shakespeare as much as the next girl,” she wrote in a 2019 article for Elle.

Her interview Read Every Day gives a good sense of this. Swift speaks about her writing process in ways that make it accessible. She explains how songs come to her anywhere and everywhere, like an idea randomly appearing “on a cloud” that becomes the first piece in a “puzzle” that will be assembled into a song. She furtively whisper-sings song ideas into her phone when out with friends.

In her acceptance speech for the Nashville Songwriter-Artist of the Decade Award in 2022, Swift explained how she writes in three broad styles, imagining she is holding either a “quill”, a “fountain pen”, or a “glitter gel pen”. Songcraft is a joyous challenge for her.

If, as teachers of literature, we are too proud to credit Swift’s plainly expressed love of English (regardless of whether we like her songs or not), we are likely missing something. To bluntly rule her out of the English classroom feels more absurd than allowing her in.

Clio Doyle, a lecturer in early modern literature, has summarized Swift’s suitability for English in a recent article which concludes:

The important thing isn’t whether or not Swift might be the new Shakespeare. It’s that the discipline of English literature is flexible, capacious and open-minded. A class on reading Swift’s work as literature is just another English class, because every English class requires grappling with the idea of reading anything as literature. Even Shakespeare.

Doyle reminds us Swift’s work has been taught at universities for a while now and, inevitably, the singer’s name keeps cropping up in relation to Shakespeare. This isn’t just a case of fandom gone wild or Shakespeare professors, like Jonathan Bate, gone rogue.

The global interest in the world-first academic Swiftposium is a good measure of how things are trending. Moreover, it is wrong to think Swift’s songs are included in units of study purely to be adored. Her wide appeal is part of her appeal to educators, but that doesn’t mean her art is uncritically included.

The reverse is true. Claire Hansen taught Swift in one of her literature units at the Australian National University last year precisely because this influential singer-songwriter prompts students to explore the boundaries of the canon.

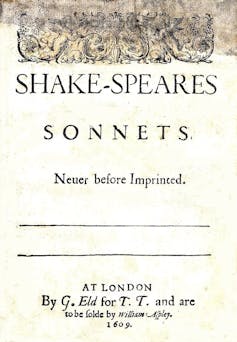

I will be teaching Midnights and Shakespeare’s Sonnets together in a literature unit at the University of Sydney this semester. Why? Not because I think Swift is as good as Shakespeare, or because I think she is not as good as Shakespeare. These statements are fine as personal opinions, but unhelpful as blanket declarations without context. The nature of English as a discipline is far more complex, interesting and valuable than a labelling and ranking exercise.

Teaching Midnights and Shakespeare’s Sonnets

I teach Shakespeare’s sonnets as exquisite poems, reflective of their time and culture. I also teach three modern artworks that shed contemporary light on the sonnets.

The first is Jen Bervin’s 2004 book Nets. Bervin prints a selection of the sonnets, one per page, in grey text. In each of these grey sonnets, some of Shakespeare’s words and phrases are printed in black and thus stand out boldly.

The result is a palimpsest. The Shakespearean sonnet appears lying, like fertile soil, beneath the briefer poem that emerges from it. Bervin describes this technique as a stripping down of the sonnets to “nets” in order “to make the space of the poems open, porous, possible – a divergent elsewhere”. The creative relationship between the Shakespearean base and Bervin’s proverb-like poems proves that, as Bervin says, “when we write poems, the history of poetry is with us”.

The second text is Luke Kennard’s prizewinning 2021 collection Notes on the Sonnets. Kennard recasts the sonnets as a series of entertaining prose poems. Each poem responds to a specific Shakespearean sonnet, recasting it as the freewheeling thought bubble of a fictional attendee at an unappealing house party. In an interview with C.D. Rose, Kennard explains how his house party design puts the reader

in between a public and private space, you’re at home and you’re out, you’re free, you’re enclosed. And that’s similar in the sonnets.

The third text is Swift’s Midnights. Unlike Bervin’s and Kennard’s collections, in which individual pieces relate to specific sonnets, there is no explicit adaptation. Instead, Midnights raises broader themes.

Deep connection

In her Elle article, Swift describes songwriting as akin to photography. She strives to capture moments of lived experience:

The fun challenge of writing a pop song is squeezing those evocative details into the catchiest melody you can possibly think of. I thrive on the challenge of sprinkling personal mementos and shreds of reality into a genre of music that is universally known for being, well, universal.

Her point is that the pop songs that “cut through the most are actually the most detailed” in their snippets of reality and biography. She says “people are reaching out for connection and comfort” and “music lovers want some biographical glimpse into the world of our narrator, a hole in the emotional walls people put up around themselves to survive”.

Midnights exemplifies this. It is a concept album built on the idea that midnight is a time for pursuit of and confrontation with the self – or better, the selves. Swift says the songs form “the full picture of the intensities of that mystifying, mad hour”.

The album, she says, is “a journey through terrors and sweet dreams” for those “who have tossed and turned and decided to keep the lanterns lit and go searching – hoping that just maybe, when the clock strikes twelve […] we’ll meet ourselves”.

Swift claims that Midnights lets listeners in through her protective walls to enable deep connection:

I really don’t think I’ve delved this far into my insecurities in this detail before. I struggle with the idea that my life has become unmanageably sized and […] I just struggle with the idea of not feeling like a person.

Midnights is not a sonnet collection, but it has fascinating parallels. There is no firm narrative through-line. Nor is there a through-line in early modern sonnet collections such as Shakespeare’s. Instead, both gather songs and poems that let us see aspects of the singing or speaking persona’s thoughts, emotions and experiences. Shakespeare’s speaker is also troubled through the night in sonnets 27, 43 and 61.

The sonnets come in thematic clusters, pairs and mini-sequences. It can be interesting to ask students if they can see something similar in the order of songs on the Midnights album – or the “3am” edition with its seven extra tracks, or the “Til Dawn” edition with another three songs.

Public domain.

Paul Edmondson and Stanley Wells, in their edition of All the Sonnets of Shakespeare, say Shakespeare’s collection is “the most idiosyncratic gathering of sonnets in the period” because he “uses the sonnet form to work out his intimate thoughts and feelings”.

This connects very well with the agenda of Midnights. Both collections are piecemeal psychic landscapes. The singing or speaking voice sometimes feels autobiographical – compare, for example, sonnets 23, 129, 135-6 and 145 to Swift’s songs Anti-hero, You’re On Your Own, Kid, Sweet Nothing, and Would’ve, Could’ve, Should’ve. At other times the voices feel less autobiographical. Often there is no way to distinguish one from the other.

Swift’s songs and Shakespeare’s Sonnets are meditations on deeply personal aspects of their narrators’ experiences. They present us with encounters, memories, relationships, values and claims. Swift’s persona is that of a self-reflective singer, just as Shakespeare’s is that of a self-reflective sonneteer. Both focus on love in all its shades. Both present themselves as vulnerable to industry rivals and pressures. Both dwell on issues of power.

Close reading

Shakespeare’s sonnets are rewarding texts for close reading because of their poetic intricacy. Students can look at end rhymes and internal rhymes, the way the argument progresses through quatrains, the positioning of the “turn”, which is often in line 9 or 13, and the way the final couplet wraps things up (or doesn’t).

Public domain

The songs on Midnights are also rewarding because Swift has a great vocabulary, a love of metaphor, terrific turns of phrase, and a strong sense of symmetry and balance in wording. More complex songs like Maroon and Question…? are great for detailed analysis.

Karma and Mastermind are simpler, yet contain plenty of metaphoric language to be unpacked for meaning and aesthetic effectiveness. Shakespeare’s controlled use of metaphor in Sonnet 73 makes for a telling contrast.

The Great War, Glitch and Snow on the Beach are good for exploring how well a single extended metaphor can function to carry the meaning of a song. Sonnets 8, 18, 143 and 147 can be explored in similar terms.

Just as students can analyze the “turn” or concluding couplet in a Shakespearean sonnet to see how it reshapes the poem, they can do the same with songs on Midnights. Swift is known for writing effective bridges that contribute fresh, important content towards the end of a song: Sweet Nothing, Mastermind and Dear Reader are excellent examples.

Such unexpected pairings are valuable because they require close attention and careful articulation of what is similar and what is not. Shakespeare’s Sonnet 129, for example (the famous one on lust), and Swift’s Bigger than the Whole Sky (a powerful expression of loss) make for a gripping comparison of how intense feeling can be expressed poetically.

Or consider Sonnet 29 (“When in disgrace with fortune and men’s eyes”) and Sweet Nothing: both celebrate intimacy as a defense against the pressures of the public world. How about High Infidelity and Sonnet 138 (where love and self-deception coexist), considered in terms of truth in relationships?

There is nothing to lose and plenty to gain in teaching Swift’s Midnights and Shakespeare’s Sonnets together. There’s no dumbing-down involved. And there’s no need for reductive assertions about who is “better”.![]()

Article written by Liam E Semler, Professor of Early Modern Literature, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

In 400 years, if she’s still listened to.